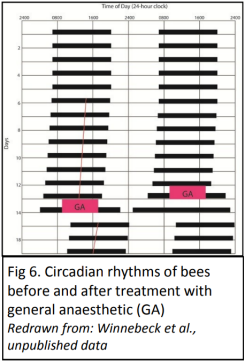

When people wake up from a general anaesthetic they often seem confused about what time of the day it is, especially how much time has passed. This suggests that general anaesthesia somehow affects our sense of time. Guy’s research team are interested in studying this phenomenon in order to potentially better manage the care of patients who undergo a general anaesthetic.

Significant advances in understanding of how biological systems work can be made by studying model organisms. The classic model organism is the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, but it is not the only one. Guy’s research group uses the honey bee, Apis mellifera, to investigate how general anaesthesia may affect our perception of time.

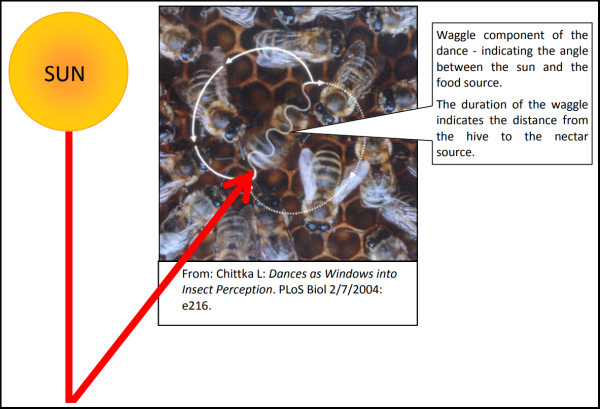

The honey bee is unique in the animal kingdom in that they have a ‘continuously consulted clock’. This means that bees are able to ‘consult’ their clock at any time to very accurately determine the exact time of the day. This clock forms the basis of their time compensated sun-compass. Bees navigate using this sun compass. They know where the sun should be at any time of the day and use this to determine the compass directions of a nectar source.

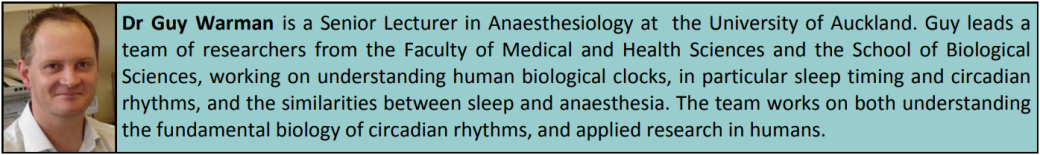

On finding a good nectar source the bee will fly back to the hive and perform a waggle dance in the darkness of the hive. This dance informs other forager bees in the hive of the direction and distance of the nectar source. The angle of the ‘waggle’ component of the dancing bee (with respect to the vertical) is exactly equal to the angle between the sun and the food source.

As the sun moves across the sky over the course of the day, the dancing bees change the angle of their dance so that they are still communicating the correct direction of the food source. They do this by consulting their internal clock and adjusting the angle of the dance accordingly.

Guy and his colleagues Dr James Cheeseman and Dr Craig Millar (from the University of Auckland) together with collaborators from the Free University of Berlin, used the fact that bees have a continuously consulted clock to model how general anaesthesia affects our sense of time.