Research carried out by Lisa and her team has focused on determining the genetic origins of animals and plants that are known to be associated with human settlements in the Pacific. These are known as commensal plants and animals because they have a close relationship with humans – as food items, companions, or because they are important for other cultural reasons. Examples of these animals include rats, pigs, dogs, and chickens. Importantly these animals cannot get from one island to another unless they are taken there by humans, therefore scientists can track the movements of the humans by tracking the movements of these commensal animals that travelled with the humans.

The first commensal animal that Lisa’s team studied was the Pacific rat or Kiore (Rattus exulans). Kiore is a good animal for this because:

- It was often intentionally transported in colonising canoes as a source of food

- It cannot swim so can only get to new islands by being carried in canoes with people

- It reproduces rapidly and thus accumulates mutations faster than humans

- It is a different species from the European rats that were introduced later and therefore cannot interbreed with them. This means any current populations of Pacific rats are direct descendants of the original populations

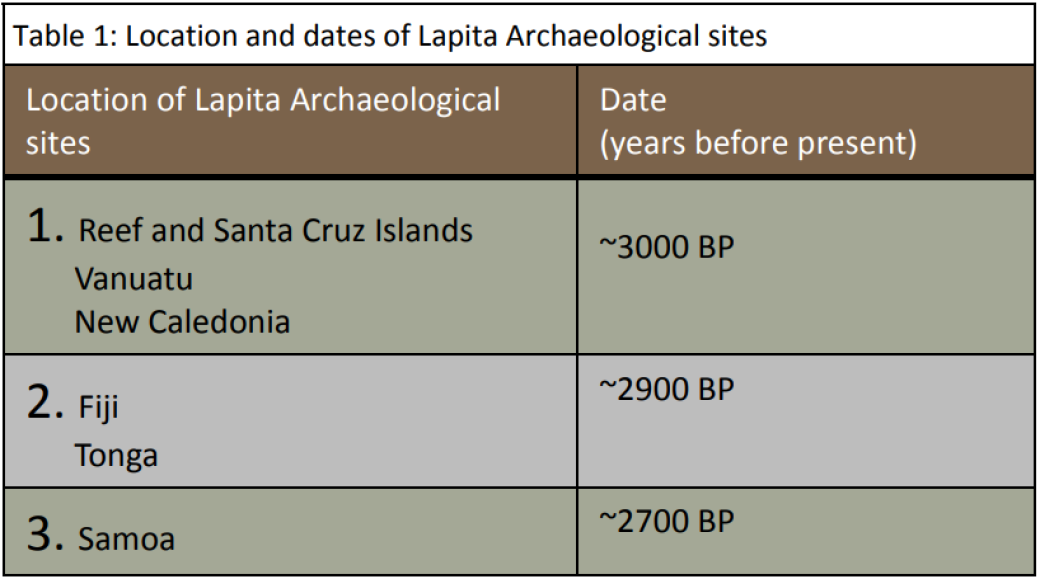

- Remains of Pacific rats appear in the earliest layers of archaeological sites associated with Lapita people and are found in all sites associated with Lapita and later Polynesian settlement

Molecular Biotechnologies Offer Advances in Understanding

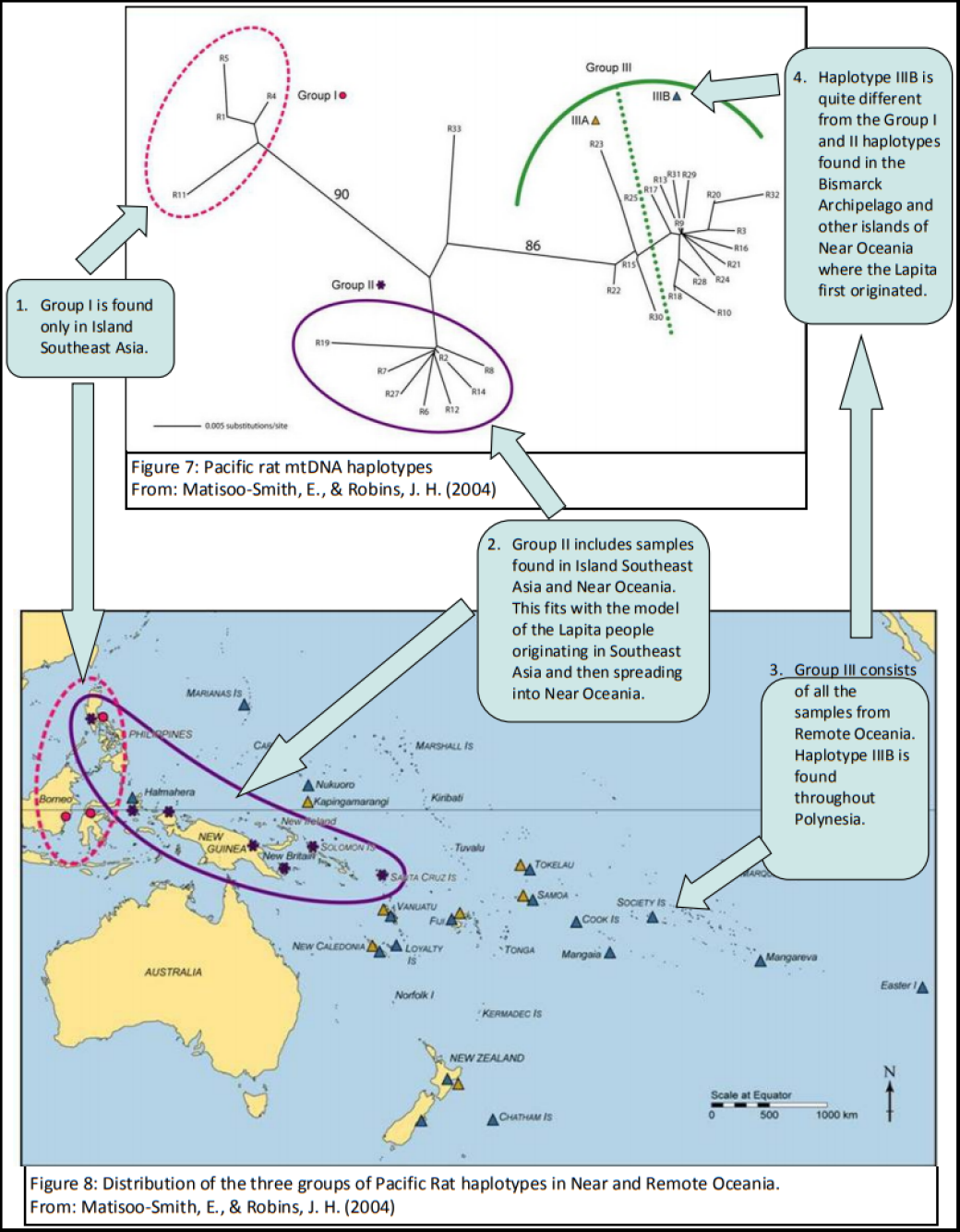

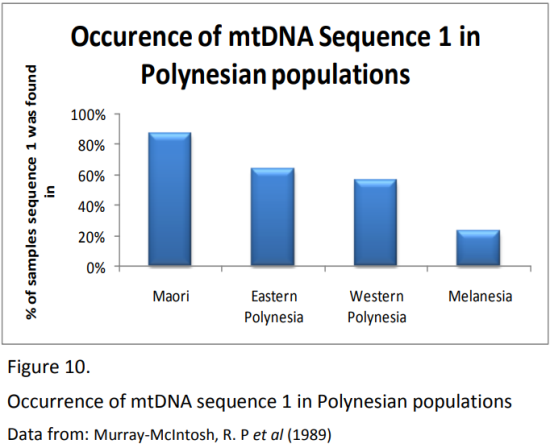

The first study looked at the variation in the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of living populations of Pacific rats from islands around the Pacific. mtDNA is inherited only from the mother, therefore there is no mixing with the father’s DNA or recombination during meiosis. This means that differences in the mtDNA due to mutation can be traced back through the generations. Scientists use the variation in the mtDNA to work out the relationships between different populations.

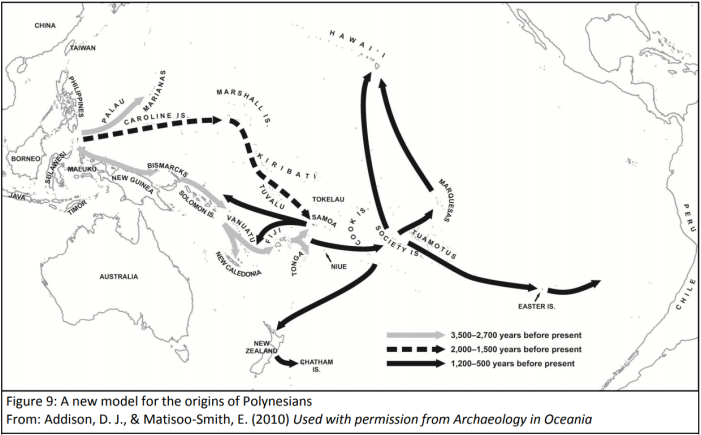

The results of this study suggested that it is highly likely that there were multiple introductions of the Pacific rat to the Pacific Islands. This raised the question, “did these introductions all occur at the same time or at different times?” If they were at different times then this suggests that another group of people migrated into the Pacific sometime after the Lapita people.

This question cannot be answered by studying modern mtDNA, as variation in modern mtDNA only shows different origins, - it doesn’t show the timing. Ancient DNA, however, could be used to answer this question. Ancient DNA is any DNA extracted from tissues such as bone that are not fresh or preserved for DNA extraction later. When an organism dies, the DNA molecules immediately start to break down, which makes it difficult to extract good quality DNA for analysis. The hot and wet environment found in most of the Pacific makes it just about the worst area for DNA preservation. Despite this Lisa and other Allan Wilson Centre researchers have been able to obtain DNA from Pacific samples as old as 3000-4000 years (2) .

If the age of the remains is known then the likely date of the introduction of new genetic material can be estimated. The team next investigated ancient DNA from the remains of Kiore found in different archaeological sites around the Pacific looking for patterns in the haplotypes in mtDNA. A haplotype is a combination of alleles that are located closely together.

Lisa found three distinct groups of haplotypes, - shown as Groups I, II and III in Figure 7. Three clearly different haplotypes (or genetic groups) is an indication that these populations of rats are likely to have quite different ancestral origins.