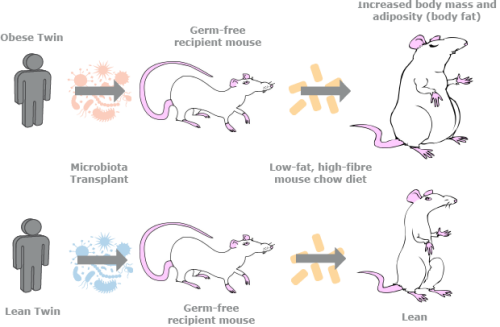

Around 35 trillion tiny, unseen organisms live in and on the surface of our bodies. These microorganisms (or microbes) include many different types of bacteria, viruses and fungi, and are collectively known as our microbiome. Microorganisms live on and in our body tissues and fluids - like skin, saliva or tears, and in the gastrointestinal tract (gut). Just like different animal species live in diverse habitats all over the world, different microbial communities live on and in various parts of the body.

We call the special collection of microbes that live in our guts the ‘human gut microbiome’. Over 400 species of bacteria are found in the human gut, most of them in the large intestine (colon). The stomach and small intestine are too acidic for bacteria to thrive. The types of bacteria most commonly found in the human gut are Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Clostridium, Escherichia, Streptococcus and Ruminococcus. Some are ‘friendly’ (for example, Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus). These microbes have a symbiotic relationship with humans as hosts. The intestine provides microbes with nutrition and a warm living environment. In return, the gut microbiome plays an important part in the way food is digested and metabolised. Other types can be harmful (for example, some species of Escherichia are pathogenic).